The impact of e-commerce

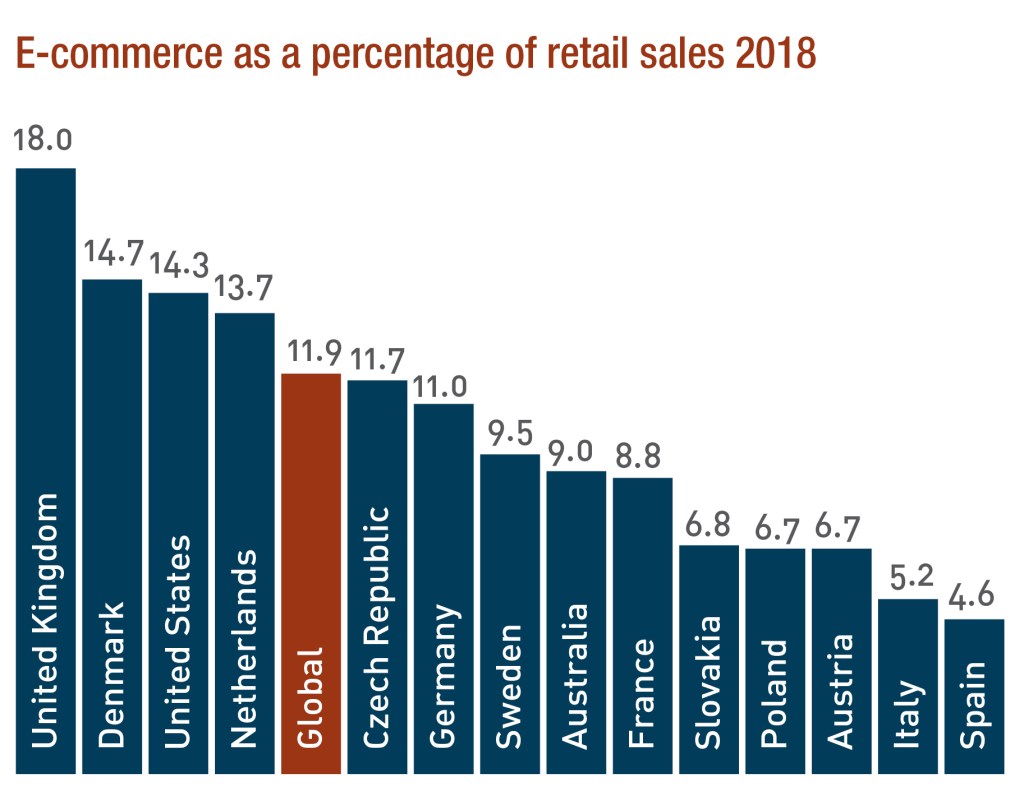

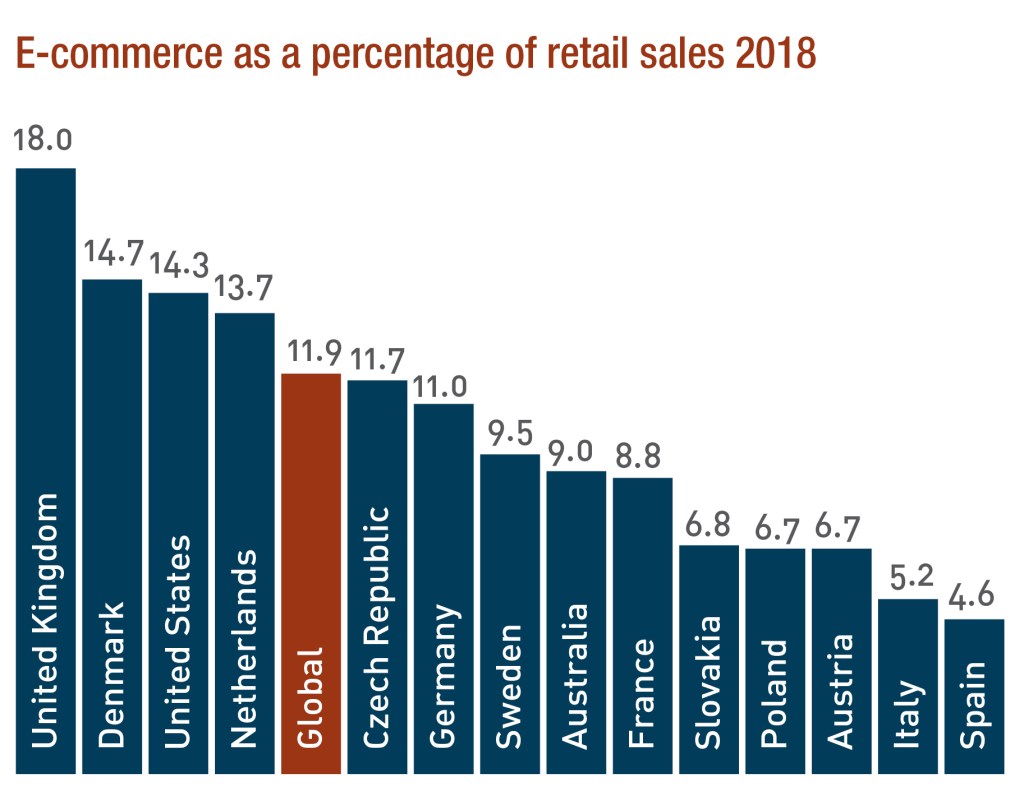

As online sales reach 11.9% of total retail sales globally, up from 7.4% in 2015 and forecast to reach 17.5% by 2021, there seems to be no sign of a reprieve for traditional operators who have not embraced the internet.

As online sales reach 11.9% of total retail sales globally, up from 7.4% in 2015 and forecast to reach 17.5% by 2021, there seems to be no sign of a reprieve for traditional operators who have not embraced the internet.

In terms of uptake for e-commerce purchase patterns, Australia lags behind about half of Europe, as well as the US, at 9% of total sales. The UK leads the pack at 18% of total retail sales, with the US sitting at just over 14%.

Between 2018 and 2023, e-commerce growth will be headlined by the United States, increasing 45.7% to US$735.4 billion per annum. France, 45.6% growth to US$71.9 billion p.a., Australia, 44.6% to US$26.9 billion p.a., and Germany, 35.6% to US$95.3 billion p.a., follow closely. The UK is anticipated to grow by less, 31.3%, to US$113.6 billion a year, but this is from a high base.

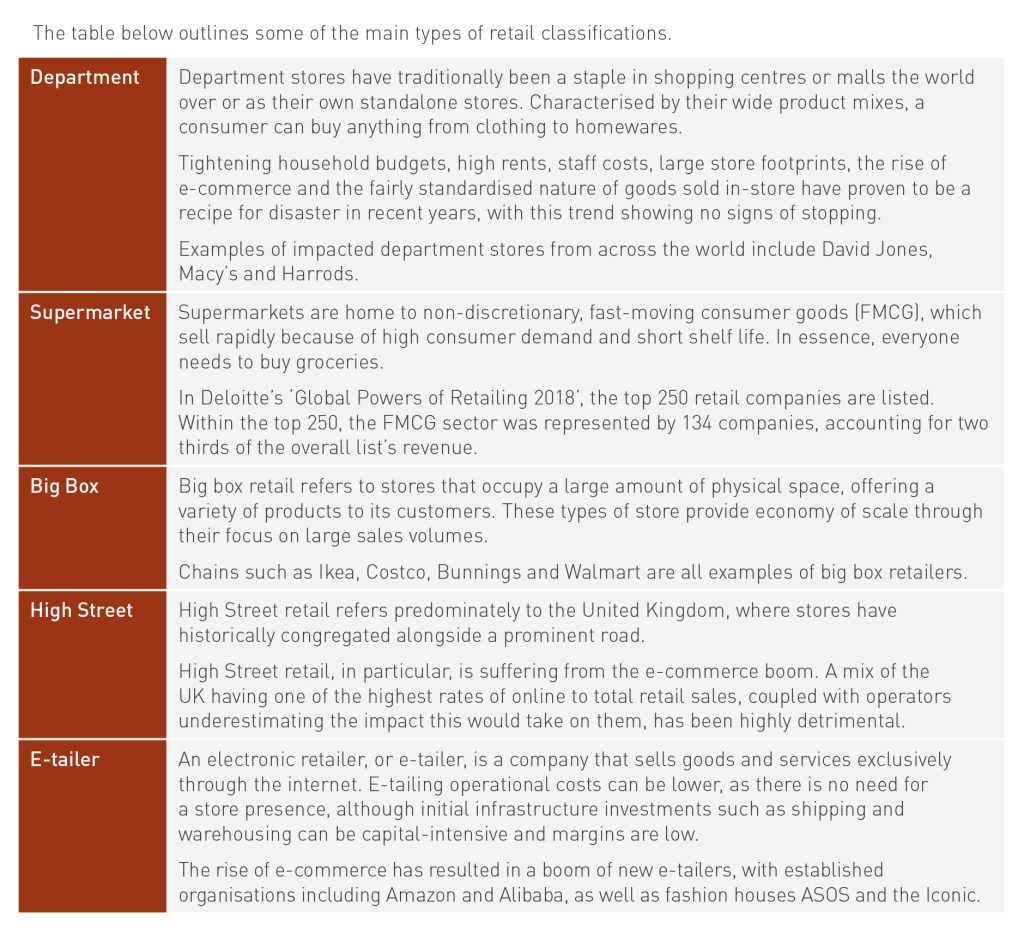

Online behemoths such as Amazon, who accounted for 40% of the United States’ online retail in 2018, continue to change the way in which consumers buy goods. The widely-held position is that this is to the detriment of traditional stores. This is evident through the demise, or seemingly impending demise of a number of big-name chains, such as Barneys New York recently filing for bankruptcy, David Jones’ owners writing down the department store’s value by $437 million, and two UK high street stalwarts, Boots and Mark & Spencer, announcing plans to close more than 300 stores between them.

The waning wealth effect

Coupled with e-commerce and cost of living pressures, the waning wealth effect also continues to impact retail investment decisions. These forces are altering consumer shopping behaviours, what they spend money on, and ultimately the performance of different retail subtypes.

Tightening of household budgets means consumers are ringfencing their non-discretionary spend while reducing their discretionary spend to the detriment of department and big box stores, as well as High Street retail.

Rental costs

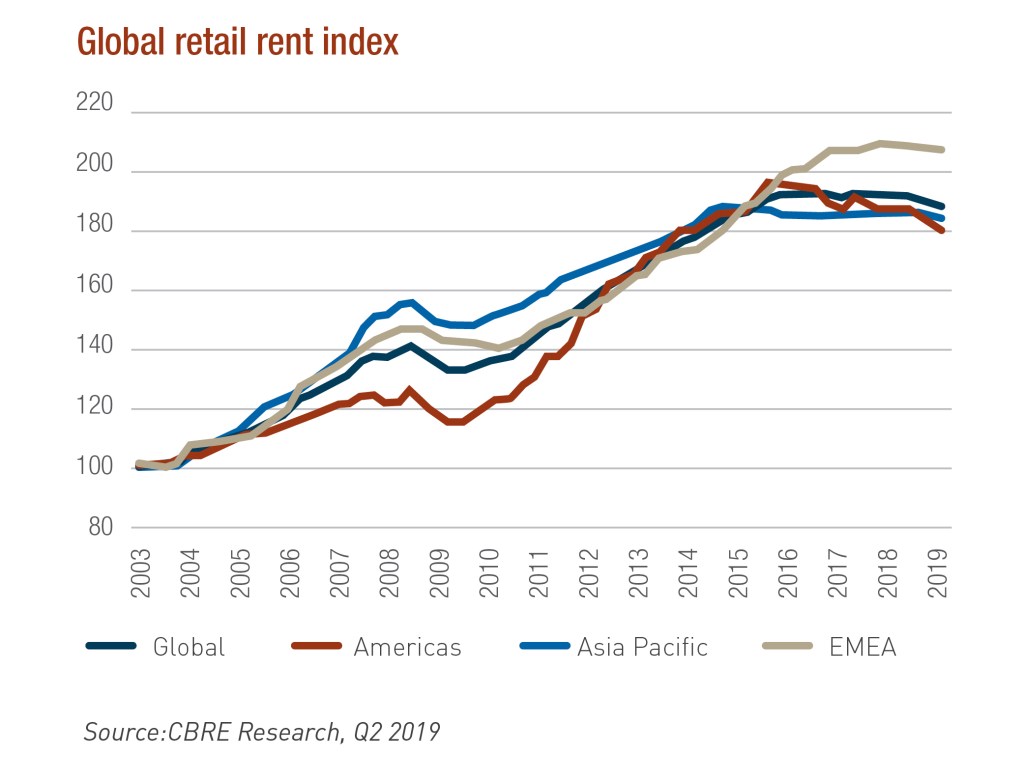

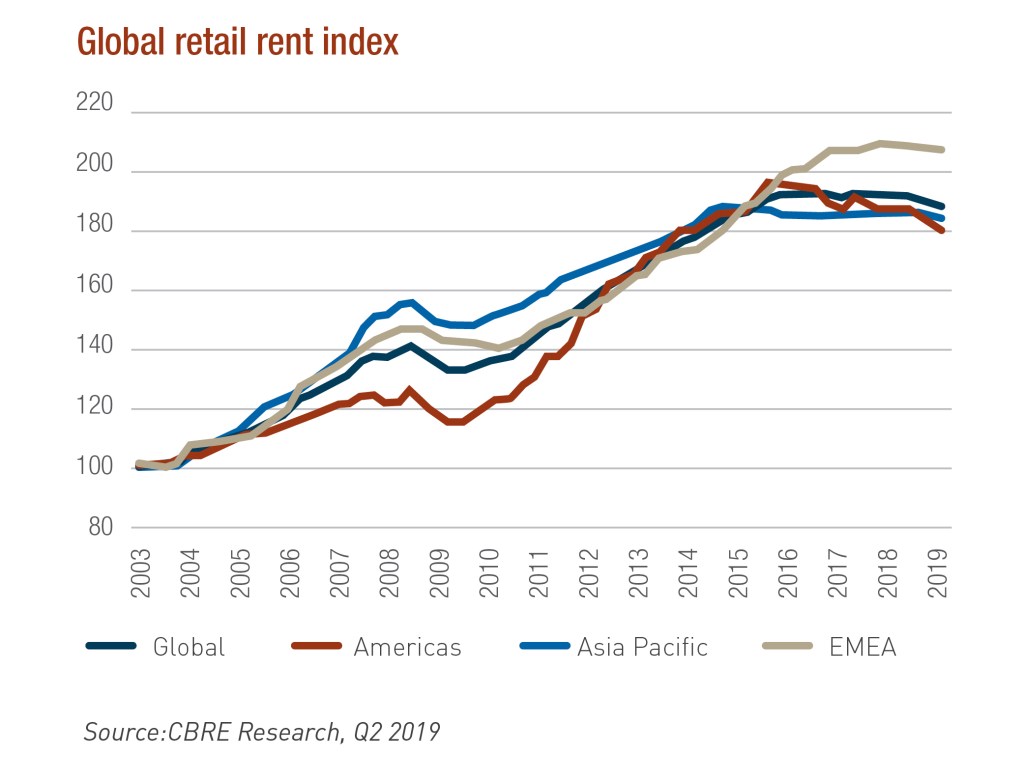

Retail rents have also begun to plateau, with downward readjustments occurring in an attempt to save struggling brick and mortar stores. However, legacy players are encumbered by high rents (often fixed and escalating), high debt levels that need to be addressed and changing consumer tastes from a discerning and cost-conscious consumer.

Even though rental growth has begun to stall, this is off the back of decades-long growth. For example, the most expensive retail location on earth in 1998, East 57th Street in New York, cost approximately US$425 per square foot (US$4,575 per sqm). Fast forward to 2018, and Causeway Bay in Hong Kong took top honours for the sixth time, with a top rent of US$2,671 per square foot (US$28,750 per sqm) – a six-fold increase.

City Council researchers in New York reported that average Manhattan rents rose 44% to US$156 per square foot (US$1,679 per sqm) between 2006 and 2016. Across the East River, Brooklyn retail rents averaged at least US$100 per square foot (US$1,076 per sqm) in 15 neighbourhoods as of 2017, up from three a decade prior.

The UK High Street is in a similar predicament with landlords consistently increasing rents. Retailers were on the expansion trail in the noughties, blissfully unaware the impact of e-commerce would have just over a decade later.

The retail landscape varies dramatically from country to country. The United Kingdom is the home of high street retail, where the United States is the land of not only the free, but also the shopping mall and has more shopping space per person than anywhere else in the world.

The retail landscape varies dramatically from country to country. The United Kingdom is the home of high street retail, where the United States is the land of not only the free, but also the shopping mall and has more shopping space per person than anywhere else in the world. As online sales reach 11.9% of total retail sales globally, up from 7.4% in 2015 and forecast to reach 17.5% by 2021, there seems to be no sign of a reprieve for traditional operators who have not embraced the internet.

As online sales reach 11.9% of total retail sales globally, up from 7.4% in 2015 and forecast to reach 17.5% by 2021, there seems to be no sign of a reprieve for traditional operators who have not embraced the internet.

Capital: Influx or in flux?

Capital: Influx or in flux? Omni-channel retailing

Omni-channel retailing