The 2017 Australian economic outlook

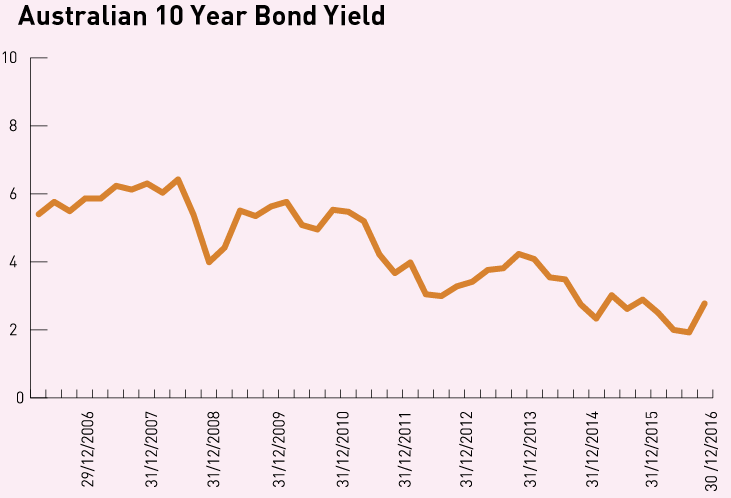

2017’s outlook is a continuation of key themes from our 2016 report. The themes have been reinforced by recent developments including volatile GDP growth, softening retail sales growth, slowing employment growth and significantly higher bond rates.

Overview

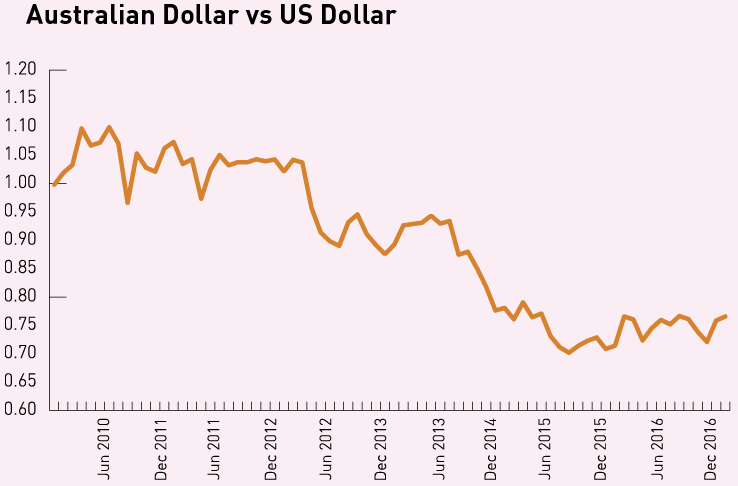

Australia’s transition to a strong post-mining boom economy continues to be slow and difficult. The lower dollar will help but there will still be significant negative shocks, headwinds and structural change. The successful outcome of the transition will depend on our ability to rebuild non-mining industries, starting with the dollar-exposed export and import-competing industries and flowing on to services.

GDP growth has come off a high of 3.1% at the start of 2016 and will continue to soften to average around 2.5% over the next three years. Employment growth, which peaked at just under 3% in 2016, will average 1% over the next three years, with the unemployment rate drifting up to 6%.

The medium term is still a story of slow structural change with many bumps on the road. However, already we can see the first signs of this change in the strength of tourism and international student education services. But there’s a long way to go before business investment comes through as a driver to strengthen economic growth and complete the transition.